(from the talk given at the 26th CONVIVIUM, Fiuggi, February 9th, 2013)

The following considerations came out from the observation of a particular rite which takes place on the last day of Carnival in Frosinone.

On this review it has been often stressed that, according to psychoanalysis, rites and myths contain, by displacement and condensation, man’s realistic or phantasmal anxieties. The ethno-anthropological point of view, too, considers rite as a socially codified form of the working out of conflicts and it is with this interpretation that we will try to understand the root of the ‘Radeca’ 1. It indicates, at the same time, the festival which is the most original, traditional and lively one in the town life and its symbol: the Radeca is an agave leaf, brandished as a pennon by the participants in the procession which heads the carnival puppet with dances and shouts with an alternation between a funeral rhythm and unrestrained little jumps until the end of the day. In conclusion they burn the Carnival, which will come back regularly in the following year when nature begins to sprout again at the end of winter.

Among the over-determinations of this rite there is the more famous ‘Carnem-levare’, which means ‘eliminate meat’. This medieval tradition is referred to Lenten fasts. Nowadays the meaning of sacrifice is represented by a funeral dance which ends with a bonfire burning a puppet. Then one goes on with religious pre-paschal privations; this ha happened until some decades ago at least.

But more recent facts connected with the practice of the Radeca go back to the end of the 18th century when echoes of the French Revolution arrived over the points of the Napoleonic Army’s bayonets into the Vatican State, where people lived as if they were still during the Middle Ages. But the attempt to export revolutionary values wasn’t very consistent and the Roman Republic, which had certainly reversed the local ruling class and expropriated church endowments, asked for new taxes. A revolt broke out. The French force reacted and an army, led by General Girardon, occupied Frosinone sacking and killing the people: it was a trauma. The following year, in 1799, another French general, Jean Etienne Championnet, would have arrived to the city just during the Carnival days. This was a period (as Chrismas, Epiphany and harvest times) when judicial activities were suspended because of an old Roman tradition. So on the Radeca day people were expecting the arrival of the new general, considered the scapegoat of his predecessor’s wrongdoing. The shout has not been changed since that time: “essigliè, essigliè!”. Probably the general did not arrived on that day, but he has remained in the rite because of the waiting, the invocation and the need to relieve aggressiveness with laughing at his caricature and with ridiculing him as a trophy to the sound of a repeated dithyramb which reaches its climax with a sacrifice and a big bonfire.

Nowadays Carnival is a festival much loved by children, who can get rid of some rules, dirty with corianders, put on grown-ups’ clothes or the ones of a loved tale and take, for one day, their dearest hero’s identity. Actually, through the play of the identifications with the referred characters, one also builds one’s Ego and the structure of one’s psyche, which establishes a relationship with the Id instincts, with the Super-ego requests and deals with reality. What’s better for a little girl than being Cinderella, the child who is exploited by all the women in the house, but who succeeds in obtaining the recognition of her insuperable female charm, which makes her the beloved girl by Prince Charming? Carnival can do all this: the realization of Oedipal wishes only for one day: then repetitions will get back.

Frustration and fulfilment, death and life always run after each other in the obsessive rhythm of the music of Carnival, whose most ancient origins go back to the Dionysian procession: the dithyramb.

“Evoè! Evoè!” 4, they cried during processions: a cry as a hymn to life, which never ceases passing and always revives with a new season like the continuous cycle of the death-life instinct.

“Essigliè! Essigliè! is today’s cry of the propitiatory dithyramb of the ithyphallic procession which makes explicit, in the dialect of Ciociaria, as it follows:

“I s’è ammosciata la radeca (“and the radeca has become soft)

nen s’aradrizza chiù” (it doesn’t rise any more”)

where the reference to the propitiation of fertility is manifest.

We are so introduced to the Dionysian origins of the Radeca festival.

A reference to this speech on Carnival is already found in “ Maenads”, one of the first articles published on this journal; that piece of work spoke about women who arrived to hospital during the night in the grip of a wild fury. These women’s characteristics and symptomatology had common elements which overstepped the diagnosis: they were histrionic and seducing, but above all with a motor prevalence which was made even more manifest by the attendant use of alcoholic drinks or other psychoactive substances.

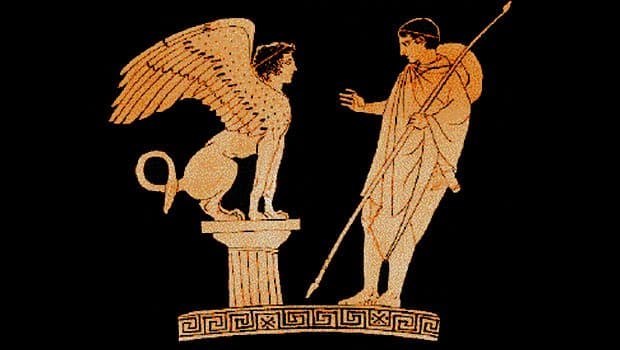

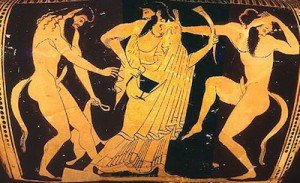

On the other hand, fallen into the grip of the intoxicating effects of the fermented juice of grapes, which began being grown between 10000 and 8000 years ago, Dionysian mysteries were really fierce not only because of sexual acting out without control but also because of assaults and killing The most striking example of this wild, voracious and cannibalistic characteristic is represented by “The Bacchantes” by Euripides, in which the author says that Penteo, the king of Thebes, had tried to control the riots provoked by these rites that denied Dionysus’ divine nature and forbid his cult. But he met with the drastic opposition of the priestesses, among whom there were his mother Agave and his sisters, who were raging on Mount Citerone 5 by quartering herds of cattle, abducting children and spreading panic. Penteo himself met with a terrible death: his drunken mother and sisters did not recognize him and quartered him. By letting Agave and her daughters take part in the murder of Penteo Euripides shows what a condition of alteration of psychic functions is caused by alcohol: affectivity is perverted, perception is made unreliable and the passage to acts becomes a rule. But Euripides also underlines what ferocity can be hidden in family relationships, which doesn’t surprise even nowadays, if one takes into consideration the so many brutal murders which happen in the family with or without the boost of modern drugs.

F. Nietzche puts forward some interesting observations about the connection between Dionysian spirit and tragedy. The Dionysian phenomenon in Greek culture and in Occidental culture represents a vital force just because of its aspects of destabilization, disorder and disorganization: an achievement of life.

In other words: when entropy goes up, some amount of energy, which becomes potentially available, is liberated .

Quite the reverse, in Apollonian spirit, which is static and contemplative, there is a predominance of death.

At the bottom of destruction Nietzche finds the joy of inexhaustibility.

In his work “Beyond the Principle of Pleasure” Freud speaks about a rebound effect from a death drive to a life drive (and viceversa) with that succession of predominance of the former or of the latter, which, in micropsychoanalysis, we have inscribed in a unique drive: the death-life drive.

And Nietzche names “Dionysian” the cyclic recurring.

It is Dionysian “the tragic poet’s spirit, which, besides terror and pity, is the eternal joy of becoming, which also includes the joy of annihilating….. “

In the continuous becoming of seasons, nature’s gifts and abuses, the cheerfulness and the ferocity of Dionysian processions and of the Radeca festival we can find the same representation of the instinctual cycle.

Gioia Marzi ©

(Translated by Concetta Violante)

Notes:

1 – The word ‘radeca’ means ‘root’ and in the Radeca festival it is symbolized by an agave leaf.

2 – The ‘Rione Giardino’ is a district in Frosinone; ‘giardino’ means ‘garden’.

3 – ‘Radecari’ are the participants in the Radeca festival.

4 – ‘Evoè’ (from Greek ‘eu’: good): ‘long live him’.

5 – ‘Citerone’ is the name of a mountain in antique Greece.

Bibliography:

Anati: “L’epoca dei sogni”

Aristotele: “De arte poetica”

De Martino E.: “Morte e pianto rituale”

Kerenyi K.: “Dioniso. Archetipo della vita indistruttibile”

Freud: “Al di là del Principio di Piacere”

Graves: “I Miti Greci”

Nietzche: “Ecce homo”

Tartari: “Rappresentazione del mondo nella Grecia Arcaica”.

La Dott.ssa Gioia Marzi è nata a Roma il 30 maggio 1952.

Psichiatra e micropsicoanalista, dal 1980 lavora presso il Dipartimento di Salute Mentale di Frosinone e, dal 2005, è responsabile del Servizio per i Disturbi Alimentari e Psicopatologia di Genere. Docente presso il corso di Psicologia e infermieristica in Salute Mentale – Modulo: Psichiatria – Universita’ La Sapienza – Roma. Ha una vasta esperienza di psichiatria forense in materia di violenze e abusi sulle donne e sui minori. Autrice di numerose pubblicazioni scientifiche, collabora con la rivista Scienza e Psicoanalisi curando la rubrica di psichiatria dal 1999.

Esercita a Frosinone e a Roma dal 1985.